18. Fragments of Faith and Compassion

Paul found himself buried under the fragments of his knowledge and his morals. But Paul never tried to build up a new, comfortable house out of the pieces. He lived with the pieces. He realized always that fragments remain fragments, even if one attempts to reorganize them. The unity to which they belong lies beyond them. It is grasped, but not face to face.

How could Paul endure life which lay in fragments? He endured it because the fragments bore a new meaning. The power of love transformed the tragic fragments of life into symbols of the whole. (Paul Tillich, “Knowledge through Love.”)

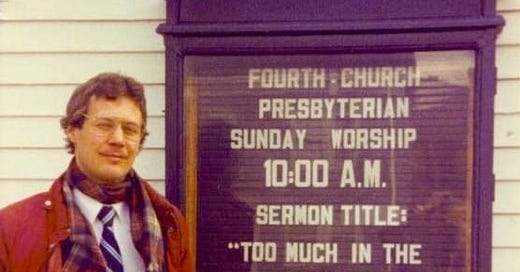

As a self in the journey of recovery, I began Christian ministry in February 1986 at Fourth Presbyterian Church in South Boston. My guest preaching in January led to a call as part-time pastor while still working at City Mission Society. Emily Chandler was my predecessor. She was a fellow graduate of Harvard and a woman of fire and truth telling. God has blessed me with many such women in my life.

Bob and Joanie showed up at the door one morning during my first week. They rang the bell. “Hi Pastor Mike—we were wondering, can we hold an AA meeting here? There are no meetings on this side of town. But there’s a ton of addiction in the neighborhood.”

They asked for one meeting a week. Soon there were three: Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous.

I sat in on some meetings. I remember hearing one woman say she lost her job, she lost her children, then she lost her sanity. At Mass Mental she got down on her knees and turned it over, surrendered her will and her life to God. Now she was beginning again, getting up on her feet—living with a new purpose, friends, and God consciousness she never could have anticipated.

This was a vision for us all.

A man in the neighborhood complained about the lack of parking on the street because of the AA meetings. I said, “Come in and see. Hear how people’s lives are being changed, turned around.”

He said he wanted his parking space.

When I left the church five years later, he walked over to my car. “There’s a new regime here now, Michael. We’ll get them out.”

I remember feeling out of control. I got in my car. I prayed the serenity prayer. I called church leaders.

The groups are still meeting at the church today.

Five months into my work in South Boston, on June 1, Coleman Brown preached at my ordination service at Fourth Presbyterian Church. Valerie gave the charge. It was 95 degrees that day with no air conditioning. It was the first ordination at Fourth Church anyone could remember.

At the service were persons who were homeless, Rick, Pete, Mark.

At the service were my divorced parents, Roderick and Doris.

There were good friends, Nicole, Young mi, Andrea, Ellen, Kiko, David, Wayne.

There were church leaders Phyllis, Bill, Angie, Laughlin, Libby. I didn’t know it then, but several future leaders—Ruth, Eleanor, Margaret, Helen, Frank, Erma—were present that day just out of curiosity.

Coleman had pastored an urban Presbyterian church in Chicago where Martin Luther King Jr. had visited and preached. He was a man of holy fire, with lightning in his eye. Along with Valerie (whose manuscript I do not have), he was the right person to speak that day.

He concluded with these words:

“Our sins and our sorrows and the power of death are where either we break into despair or we break into Christ’s new life. Our sins and our sorrows are where all our great gifts are hidden, above all the gift of our compassion, the gift of our love.

So I am coming on in now. Catch the points again: Thanks for everybody here this afternoon—and for those who are not here and—yet who are.

Compassion . . . that’s the main point isn’t it? To learn compassion. How to be compassionate.

So tame your tongues. Together, let us give up gossip.

Instead … pray your own real words. The Spirit makes a home in us, intercedes for us and brings us back to life.

And now include Michael Granzen in your love even more than ever you have before.

But love one another in the congregation, in the presbytery, in the struggles. Love one another—in joy and in sorrow, in success and in conflicts and failure.

Indeed, your love—“tough love,” at times—but your love for one another will be as important to Michael Granzen as loving him directly. That will be to make the gospel credible to him, to make a believer of him—and give him joy and power in his ministry—that we love one another!

But don’t do that with condescension as if you “had it together.” Let us learn to love one another as fellow-sinners and sufferers, on our way to die—even as we are. Let us love one another as God loves each of you—and loves me.

Remember Jesus’ haunting question, “When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith?” When Christ comes, will Christ find faith? (see Luke 18:8).

When the battle of life is over and our work is done and we are fully revealed in the presence of God, will there be found in us faith and hope and love? That is Jesus’ question.

Even so, come, Lord Jesus!”

After ordination, midweek Bible study began. We used the “Transforming Bible Study,” written by Walter Wink. The theme was unmasking and naming our enemies within and without in God’s humanity. Jesus’ teaching on the splinter and beam was a central text (Matt 7:3–5).

The Bible study grew from five to twenty to forty. We had to break into small groups. Wednesdays began to exceed in size the Sunday worshipping community. One man told us he thought the honest give-and-take dialogue, hard questions, and earthy prayers of the Bible study far exceeded his experience of Sunday worship, which focused on proclamation. We listened. Participatory singing, improvisational joys and concerns, and community meals were soon added to Sunday worship. For worship to have integrity, it must reflect the diversity of its community.

One Sunday during the period of “joys and concerns,” a woman announced she was one year sober, and the congregation burst into applause. After church, an old timer, Phil, took me aside.

“You are way over the line. This no longer resembles our church. This is—unPresbyterian!”

I had learned from my experience in recovery to not react, but breathe and respond. I waited.

“Phil, so when would you think it appropriate to applaud in church?”

He thought for a moment. “Well maybe at the end of World War II. And, then, just maybe.”

The applause continued, and Phil kept protesting.

He would welcome and escort people to their seats on Sunday morning. He was the maitre d’ of the congregation. He loved people, he loved worship, and he loved tradition. It took him a while, but eventually he learned to love people and worship more than tradition. Not without resistance.

He offered to play the entire 1933 green hymnal so I could become better acquainted. He would play five hymns each Wednesday morning, so I could then pick two for the evening Bible study. I did this for two weeks and then opted out.

There was a moment soon after at a session meeting in June. A woman from AA wanted to join the church. Her name was Shirley. She wore heavy pock marks and scars on her face. She talked slowly in a thick working-class Boston accent. We spoke with her and then I asked three questions, “Who is your Lord and Savior? Do you trust in him? Will you give of yourself to Christ’s church wherever you may be?”

She answered in the affirmative. And then left the room.

A motion was made and seconded to receive her by affirmation of faith. I asked for questions and discussion. Phil spoke up. I don’t remember much of what he said, but his closing words were, “We don’t want people like this joining our church. It will change who we are.”

There was a stunned silence.

“Phil, if you want the church to be a country club then change the name and get a country club director. But this is a church. You were at my ordination. Shirley has answered the required questions. She comes to the Bible study and Sunday worship. She affirms she is a disciple of Jesus Christ. Any other questions or discussion?”

I don’t remember what was said next, but the session voted seven to one to receive Shirley as a new member. When she came back into the room, there was an awkward silence. One woman took off the cross from her own neck and put it on Shirley.

The next morning, I was sitting alone in my tiny office. I could barely close the door with all the books. There was a knock. Phil stood high above me, all six foot two.

“Good morning. I do have a question. Do you want me to punch you in the face before or after we talk?”

“Well, why don’t we talk first.”

We spoke for over an hour. Then we went to lunch. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

At a later session meeting, Phil said he would give the church a significant sum of money to restore and paint the whole building if he could pick the colors, including painting the front doors red. He liked that color.

The session voted unambiguously against it.

Five years later, when I was leaving Fourth Church to go to Iona, I went up to Phil by my car at the edge of busy Fourth Street. It was the last time I would see him.

“Well, Phil,” I said, “You’ve given me a lot of advice during my time here.”

“Yes, Michael. And you didn’t listen to one damn bit.”

We embraced.

Years later, when I was visiting Boston for the American Academy of Religion’s Annual Meeting, I drove over to Fourth Church. It was a grey November afternoon in Southie. The salt air blew in from the sea. Phil had been dead now for many years. The church had bought a second adjacent building on Vinton Street for youth ministry. Teenagers—Black, brown, and white—flowed up and down the stairs like a river, talking together. I walked over to the front of the building where Phil and I had bid goodbye. I looked over. The church stood out now with fresh white paint against the grey sky. The doors were all bright red.

On Mourning and Metanoia

Amy had a secret. I didn’t know this. She was in her late seventies and would invite me to her home for Lithuanian suppers before the Bible study. We would pick up other ladies on the way to the Bible study and later drive them home. They became the Go-Getter’s woman’s group. They were mostly widowed women who were now coming into their own. Every Wednesday, Amy and I would talk over supper, then pray.

I would lift up fragments of what she shared. Awkwardly, imperfectly. Then we would sing from Amy’s childhood Lutheran hymnal. We did this for six weeks. Each week while I prayed, Amy would cry. Then we would sing. As the weeks went by, she began to sob. In my last week, she shared a deep secret from her childhood. I prayed. She wept. We sang.

“If ever I loved Thee my Jesus 'tis now”

Years later after I had moved to Elizabeth, when Amy was dying at Boston City Hospital, she left a phone message for me. She sang the song.

Ralph had fought in North Africa in World War II. He was now in the hospital with multiple physical problems. He wanted out. He wanted to ride his bicycle again by the waterfront. He shared words with me about driving a Sherman tank with General Patton in the North African desert. The tank became stuck on a cliff edge, Germans were all around. He was the driver and had to slowly back the tank off the cliff. One mistake and he and his crew would fall to their death on the rocks below. He said he did it very slowly, while praying, by God’s grace. I said maybe he had to pray again for the grace and courage to get off this cliff. Somehow, he got off this second cliff, too.

Ruthie was dying. Her daughters were coming to say goodbye. Her nickname was the General. She was a natural leader like none other. I knew she watched my back.

I said to her, “Turn it over, Ruthie, God won’t let you down now.” She smiled.

“I sure hope not.”

Amy, Ruth, Ralph—together they taught me what really counts in life, and in ministry. For ministry is simply life in intensity.

As William Stringfellow wrote, “In the face of death, live humanly. In the middle of chaos, celebrate the Word. Amidst Babel, speak the truth. Confront the noise and verbiage and falsehood of death with the truth and potency and efficacy of the Word of God.”

Walking Through the Valley

God’s grace will lead us by running waters, down stony paths, and through valleys. We never walk alone.

One morning during my first year at Fourth Church, I received a phone call from Rick and Toby Gillespie-Mobley. They were the new Black pastors at Roxbury Presbyterian Church. We had started out together. As we talked, I learned that the South Boston and Roxbury churches had once been one. This year was the one-hundredth anniversary of Roxbury’s founding as a separate church. The idea emerged to hold a unity walk from Roxbury to South Boston in late September, then worship and break bread together. A minister friend, Alice Hageman, suggested we bring both sessions together to do the planning themselves. That was decisive. We met every Wednesday evening through the summer. We read scripture, we prayed, we laughed, we ate together. By late August there was unity. We were called by God to do this walk from Roxbury to South Boston. We did it.

The Monday after our walk from Roxbury to South Boston, an article came out on the metropolitan front page of the Boston Globe:

“Some 40 men, women, and children who walked from Roxbury to South Boston yesterday, holding helium filled pastel balloons and singing hymns, were celebrating history for two reasons.

Members of the Roxbury Presbyterian Church were commemorating the time 100 years ago when their church opened its doors. Before that, Roxbury residents had walked each Sunday to the Fourth Presbyterian Church in South Boston.

“It sort of got cold walking to South Boston,” said Reverend Frank Miller, minister emeritus of the Roxbury church. “They didn’t believe in taking the tram because of the Sabbath.” The nearly two mile trek of the mostly black congregation to a white congregation in South Boston was also historic because it was one way to signal an end to discord between the two communities, participants said.

“Five years ago we might not have done this,” said Reverend Toby Gillespie-Mobley, co-minister with her husband, Rick, of the Roxbury church.

“It shows that in Christ there is unity, regardless of race, color or creed,” said Gillespie Mobley, who wore a long dress and shawl to imitate clothing worn in 1886 and she walked with her four-year-old daughter, Samantha.

The exuberant group, dressed in long skirts, morning coats or striped jackets with straw bowlers, sang, “We’ve Come This Far by Faith” and other hymns as they walked from the Roxbury Presbyterian Church, on the corner of Woodbine and Warren Streets toward South Boston.

They drew the curious to door-steps and windows as they passed, escorted by two Boston police cruisers. On Dorchester Street in South Boston, an informal escort of freckle-faced youngsters on bicycles pedaled with them to the corner of Vinton Street, where the churchgoers released the balloons into the air.

Members of Fourth Presbyterian waited outside their church. “This is like a homecoming event,” said Laughlin McMillan of South Boston as he stood smiling.

Elders in the … South Boston congregation met with elders of the Roxbury church during the summer to plan the event, according to Reverend Michael Granzen, pastor of the South Boston church.

“Our folks are really excited about it. At first, they were a little apprehensive,” Granzen said. “It’s both historic and healing, but between two communities that have experienced a lot of division.”

Granzen said some members “weren’t sure how the neighborhood would react.” During the summer, however, members of the congregations got to know each other well, and the apprehension dissipated.

After the walk, the congregation celebrated during a joint service at Fourth Presbyterian. Reverend John Macinnes, director of the office of ecumenism for the Boston Archdiocese, also attended the service as a representative of Cardinal Bernard Law.” (“A Walk of History, Healing,” by Diana Alters)

The next morning, I went into my tiny office at church. There was a new message on the answering machine. I pressed the button. It was the voice of Whitey Bulger, the organized crime boss and leader of the Winter Hill Gang. Bulger’s name was later put on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted Fugitive” list as number two, just behind Osama Bin Laden.

“Reverend, we’re gonna blow up your church!” I learned later this was his signature threat. He used the same words with the owners of the nearby liquor store when they resisted selling it to him. I called one elder, who immediately came in to my office.

“You don’t know what these people are like, what they’ll do.” His hands were shaking.

I called the Boston Police. Two men arrived from the bomb squad wearing bulky suits and carrying explosive detection equipment. I told them the threat was given in the future tense. I didn’t think there were any bombs on the premises. Nevertheless, they searched all through the church, under the pews, and outside. One man turned finally and said, “Well, it’s all clear of bombs.” I thanked him.